NC Collaboratory project builds resilience after hurricane

Assistant professor Antonia Sebastian describes her work in flood modeling and flood hazard research.

Following the impact of Hurricane Helene on western North Carolina, the North Carolina Collaboratory is working with partners across state agencies, academic institutions and communities to identify areas in which research is critical to the response and recovery efforts in the region.

One project the Collaboratory is supporting is the work of assistant professor Antonia Sebastian of the earth, marine and environmental sciences department in the UNC College of Arts and Sciences.

How will your research benefit citizens of western North Carolina?

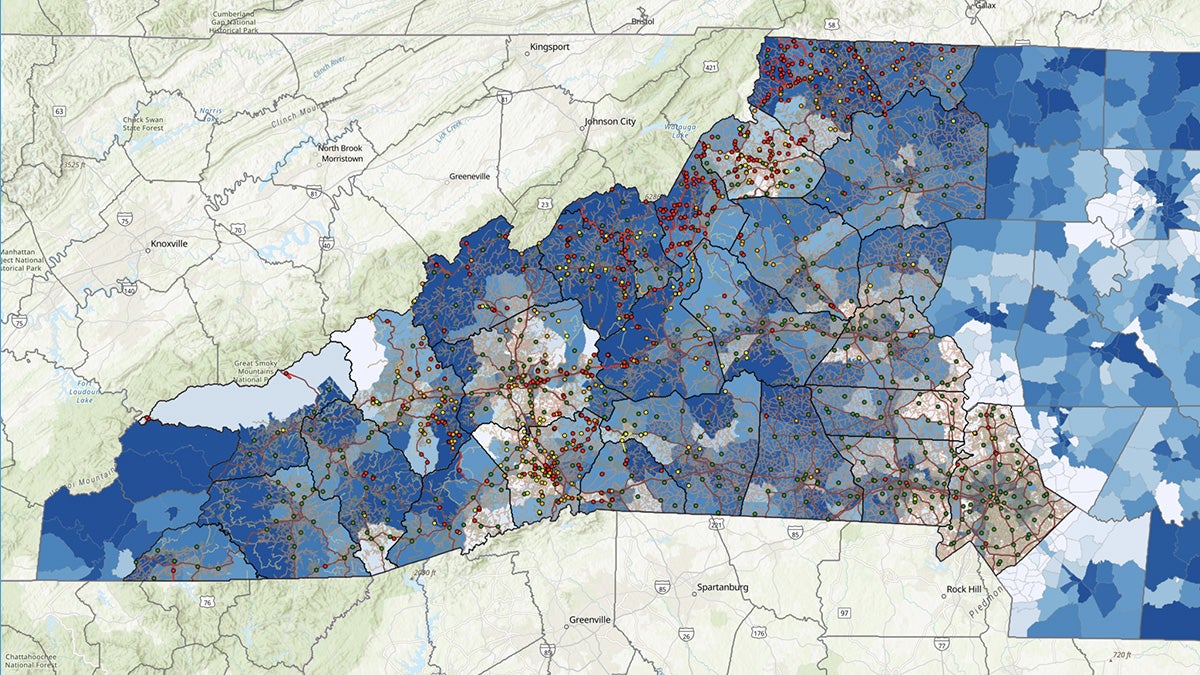

The work we are doing in western N.C. aims to address questions related to the economic resilience and rate of recovery of households and communities in the wake of Helene. Our goal is to understand what was damaged during the flood, what is rebuilt and when, and how this translates to community resilience over the long-term. In addition, we aim to develop hazard and risk information that can be used to help support state agencies, local government and communities as they make decisions about how, where and what to rebuild.

How can communities become more resilient to these storms?

Much of U.S. infrastructure is built to last for 50 to 100 years. What is built on the landscape will be there throughout much of our life and longer. Evidence points to storms becoming wetter and more intense in the future. Repeating exposure to flood events can have devastating consequences for the economic health and wellbeing of local communities. Thus, building infrastructure and housing that can withstand not only the floods of the past, but also those of the future, is critical to developing resilient communities and avoiding losses over the long term.

How did you become interested in flood modeling and flood hazard research?

I have always been excited about water and sustainability. I grew up in a part of Texas known as “Flash Flood Alley,” and several experiences with severe weather in Houston during college solidified my interest in trying to understand and model floods. My research focuses on trying to identify the places where it has flooded in the past and those where it could flood in the future.

Critical to this question is, “What makes a flood a disaster?” I am particularly interested in understanding who and what is and will be in harm’s way, and how individual- and community-scale decisions — like development or infrastructure investments — can change the trajectory of flooding (and flood risk) in a community over time. Understanding how the climate is changing and what influence those changes will have on flooding is a big part of this, too. Ultimately, my research aims to support informed decisions about living in and around flood prone areas.

What previous experience is helping guide your approach?

I’ve worked in post-disaster landscapes before – after Hurricanes Ike (2008), Harvey (2017) and Florence (2018), and after other smaller events, like the Tax Day and Memorial Day floods in Houston.

It’s important to recognize that recovery looks different across different areas, communities and for different people. In one area, businesses might be open and damaged homes repaired, but that doesn’t imply that the individuals living in these communities haven’t been affected by the event. Everyone has their own experience with a disaster and it’s important to understand that things can “feel weird” for a long time.

Working in disaster-impacted areas requires an extra level of self-awareness and empathy. Researchers: Check your privilege. Recognize that folks on the ground often know and understand so much more than you give them credit for, and that sometimes (often) the expert can be wrong.